Here’s quite an interesting chart showing the proportion of adults in the UK who use the internet.

The line does a thing that makes charts conventionally interesting: it moves from the very bottom of the graph (the early 90s, when the internet was a concept that was exciting academics and investors) to the top of the graph (the early 2020s, when the internet is an essential utility upon which public services, entertainment, huge swathes of the economy and almost everything you do depend). A lot changed, in a big and impactful way.

Here’s a second chart, which is mesmerically boring. It’s the proportion of people aged 16+ in the UK who are in work, over the same period.

The line doesn’t move very much at all. In 1990, 60% of people in the UK were in work. In 2022 that had surged – to 60.6%.

There are some small fluctuations in the data that don’t show up too well on a 0-100 axis – employment fell to 56.1% in 1993 and hit 62% in 2019. These are small percentages but huge numbers. If the proportion of people employed drops from 60% to 56% that’s millions of people out of work. But there’s not been wholesale change.

When we plot these lines together, it creates a new kind of chart, kind of in the shape of a lower case ‘f’ (at least the way my five year old is learning to write them).

I think this chart is important, because although one thing has changed dramatically and fundamentally, the other thing - a thing we might expect to be in some way affected by the dramatic and fundamental thing - really hasn’t changed at all.

The widespread adoption of the internet, which has been an absolute change (it’s gone from 0 to almost 100 and is relevant to every walk of life and economic activity) hasn’t changed our propensity to work.

We’re never going to stop working

Of course, this piece is really all about AI. Since November 2022, when ChatGPT 3.5 was released, there have been no shortage of predictions, analysis and fretting about what this means for employment.

Some of this has been deeply, obviously hyperbolic – CEOs weren’t made obsolete because an LLM can write a meeting agenda – but others much more sensible.

As the capabilities of AI expand – particularly with developments in agentic AI – more jobs are under threat. As Matt Yglesias, Susi O’Neill and others have recently explored, movements here are both rapid and non-linear, both forwards and backwards.

For example, advances in self-driving vehicles (and, more crucially, legislative updates that permit them) mean more driving jobs will be lost. The ability of generative AI to create plausible and passable images, illustrations and visualisations is threatening creative jobs. Its text generation capabilities theoretically challenges anyone who writes for a living. AI avatars create an opportunity for customer/audience facing jobs to be automated, encompassing any kind of role from call centre staff to radio hosts. Virtually any job is under threat to some extent.

In his recent piece, Yglesias argues that by the next US election developments could be such that despite all of the other things currently going on in the world, AI disruption and the policy response could be the dominant issue.

But despite the rapid developments in capability and promise, 2025 has provided several warning signs for organisations looking to rapidly drive efficiencies (i.e. replace expensive human workers with less expensive AI). Klarna replaced 600 customer support workers with AI and then reverse-ferreted, admitting that while the AI is cheaper, it’s also much less competent. IBM did the same thing.

We’ve explored this issue before in these pixels: AI is the latest dramatic technology disruption, but since at least the 1960s, none of the others have resulted in mass unemployment. The nature of work, the composition of the economy and the skills required to start and succeed all change, all the time. But the fact of our working does not.

What does this mean?

This kind of worry accompanies all new technologies. In 1997, 40% of people felt that ‘information technology was a threat to employment’.1 I’m sure it felt like it. But the proportion of the workforce employed in the IT sector has more than doubled since then, and virtually every other desk based job now has an IT component. Or in the words of Donald Trump: everything’s computer.

Clearly, AI will wreak havoc on the way we work and on what work involves. But that isn’t the same as removing the requirement or opportunity to work. Again, looking backwards provides some clues to the future.

Technology tends to create jobs as it replaces them. No jobs that exist today in SEO, ecommerce, digital entertainment, social media, information security or web development existed thirty years ago. There are literally billions of people currently employed in the podcast sector. This may or may not be a good thing, but is very much an internet-enabled thing.

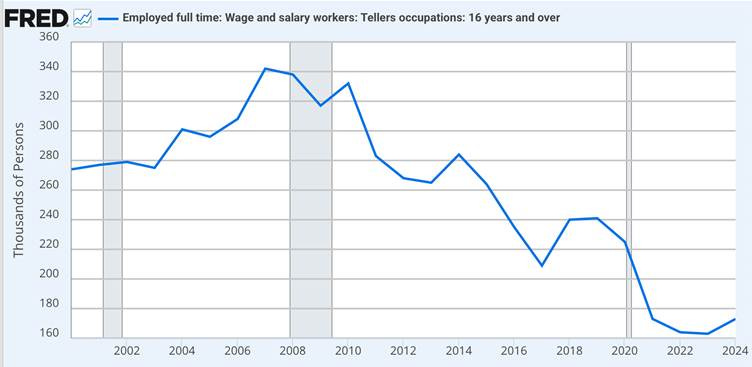

Technology takes a long time to do away with the things it makes obsolete. There’s an old example of fears that ATMs would put all bank tellers out of a job. But in the decades after ATMs were introduced (in the 1960s and 1970s), the number of bank tellers kept on increasing. Only after the global financial crash did they start declining.

That second point is worth emphasising. The internet killed a lot of things, but it killed them slowly. Teletext was retired in 2012. The last Yellow Pages was printed in 2019 and the last Argos catalogue was printed in 2020. It’s 2025, and if you want to, you can pay your council tax by cheque. By cheque.

Perhaps AI will be different. Perhaps unlike computers, or the internet, or ATMs, or pocket calculators, or automobiles, or trains, AI is the thing that is going to result in rapid mass unemployment that craters tax revenues and leads to misery and desolation.

But the lesson of the F Chart - the effing chart - is that that kind of disruption is rare. Technology changes a lot of things, but history – including recent history – suggests it changes them slowly.

More than this

Trajectory track social, consumer and technology macro trends continuously in our online Horizon Scan. For access to that, as well as our monthly Optimism Index consumer sentiment reports, monthly deep dives and archive of webinars, check out the Now & Next membership page.

Ipsos MORI - accessed via AMSR